The need for Explicit Exploration in Model-based Reinforcement Learning

In model-based reinforcement learning, we aim to optimize the expected performance of a policy in a stochastic environment by learning a transition model that includes both epistemic (structural, decays with more data) and aleatoric (noise, independent of data) uncertainty. When optimizing the policy, current algorithms typically average over both types of uncertainty. In this blog post, we discuss problems with this approach and briefly discuss a tractable variant of optimistic exploration based on our upcoming NeurIPS paper [1].

Model-based reinforcement learning

In the following, we focus on deterministic policy and environments, and finite-horizon undiscounted RL for simplicity. Please see the paper for a more general exposition. Given those assumptions the typical reinforcement learning objective is to optimize the cumulative \(r(s, a)\) over environment state trajectories of length \(N\). For any dynamics \(f\) this performance metric is given by

\[\begin{align} J(f, \pi) =& \sum_{n=0}^{N} \, r(s_n, \pi(s_n)) \\ &s_{n+1} = f(s_n, \pi(s_n) ) \\ &a_n = \pi(s_n) \end{align}\]and our goal is to find the policy that maximizes performance, that is

\[\begin{equation} \pi^* = \arg\max_\pi \, J(f, \pi). \end{equation}\]To solve this problem, typical RL algorithms replace the unknown transition model \(f\) by transition data samples from interactions with the environment. In model-based RL, we instead learn a model \(\tilde{f}\) that approximates the true transition dynamics \(f\). That is, at each episode \(t\) we select a policy \(\pi_t\) and collect new transition data by rolling out with \(\pi_t\) on the true environment. Subsequently, we improve our model approximation \(\tilde{f}\) based on the new data and repeat the process. The goal is to converge to a policy that maximizes the original problem \(J(f, \pi)\), that is, we want \(\pi_t \to \pi^*\).

Greedy Exploitation

A key challenge now lies in how to account for the fact that we have model errors, so that \(\tilde{f} \ne f\). While it is possible to solve this problem with a best-fit approximation of the model to the data, the most data-efficient approaches learn probabilistic models of \(\tilde{f}\) that explicitly represent uncertainty; be it through nonparemetric models such as Gaussian processes as in PILCO [2] or ensembles of neural networks as in PETS [3]. The end-result is a distribution of dynamics models \(p(\tilde{f})\) that could potentially explain the transitions on the true environment observed so far.

Even though both PILCO and PETS represent uncertainty in their dynamics models, in the optimization step they average over the uncertainty in the environment,

\[\begin{equation} \pi_t^{\mathrm{greedy}} = \arg\max_\pi \, \E_{\tilde{f} \sim p(\tilde{f})} \left[ J(\tilde{f}, \pi) \right]. \end{equation}\]That is, for episode \(t\) \(\pi_t^{\mathrm{greedy}}\) is the policy that achieves the maximal performance in expectation over the learned distribution of transition models \(p(\tilde{f})\). This is a greedy scheme that exploits existing knowledge (best performance given current knowledge), but does not explicitly take exploration into account outside of special configurations of reward \(r\) and dynamics \(f\) (e.g., linear-quadratic control [4]). In fact, even with our restriction to deterministic dynamics \(f\) in this blog post, this is a stochastic policy optimization scheme that effectively treats uncertainty about the transition dynamics similar to environment noise that we want to average over.

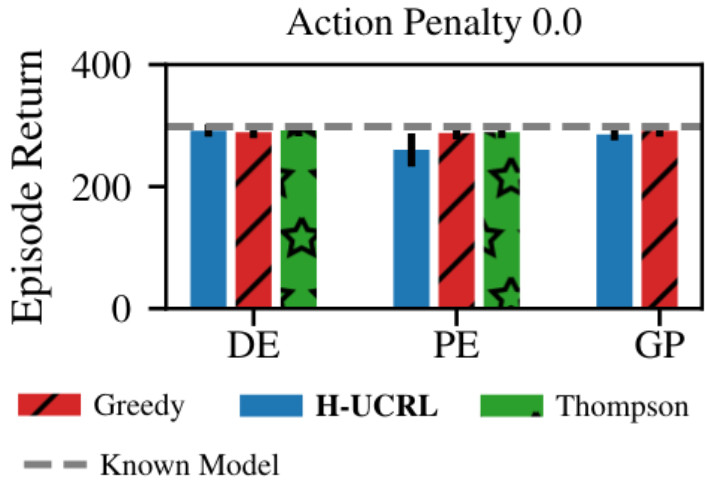

This can lead to peculiar behavior in practice. Consider the standard pendulum-swingup task with sparse rewards (we only get a reward when the pendulum is upright). In addition, we add a penalty on the norm of our actions, which is often desirable in terms of minimizing energy and jitter but also means that exploration comes at a cost. Now, during the first episode we collect random data, since we do not have any knowledge about the dynamics yet. Consequently, our learned model will have low uncertainty at the downwards position of the pendulum, but high uncertainty elsewhere in the state space. This is not a problem without action penalty, since there is still a marginal benefit to swinging up. Consequently, greedy exploitation solves that task independently of the model (DE=deterministic ensemble, PE=probabilistic ensemble, GP=Gaussian process):

However, once we add an action penality things change. Since \(\pi_t^\mathrm{greedy}\) averages over model uncertainty, the expected cost of actuating the system and swinging up seems artificially high since many of the possible dynamics in \(p(\tilde{f})\) need different control actions to stabilize at the top. In contrast, not actuating the system at all occurs zero penalty, which leads to a higher overall expected reward than actuating the system. Consequently, greedy exploration cannot solve the task.

While we focused on this simple environment here, the paper shows that this behavior is consistent for more complex Mujoco environments too.

Optimistic Exploration

To solve this problem, we have to explicitly explore and treat uncertainty as an opportunity, rather an adversary. We propose H-UCRL (Hallucinated-Upper Confidence RL), a practical optimistic exploration scheme that is both practical, so that it can be easily implemented within existing model-based RL frameworks, and has theoretical guarantees in the case of Gaussian process models. Instead of averaging over the state distribution imposed by the expectation in the greedy formulation, we instead consider acting optimistically within one-step transitions of our model.

Conditioned on a particular state \(s\), our belief over \(\tilde{f}\) introduces a distribution over possible next states. In particular, we consider Gaussian distributions so that the next state is distributed as

\[p(s_{t+1} \,|\, s_t, a_t) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_t(s_t, a_t), \sigma_t(s_t, a_t)^2)\]according to our model. Instead of averaging over these transitions, we propose an exploration scheme that acts optimistically within the confidence intervals over the subsequent states. To this end, we introduce an additional (hallucinated) action input with control authority proportional to the one-step model uncertainty \(\sigma(\cdot)\), scaled by an appropriate constant \(\beta\) to select a confidence interval (we set \(\beta=1\) for all our experiments). If we assign a separate policy \(\eta\) to this hallucinated action space that take values in \([-1, 1]\), this reduces the stochastic belief over the next state according to \(p(\tilde{f})\) to the deterministic dynamics

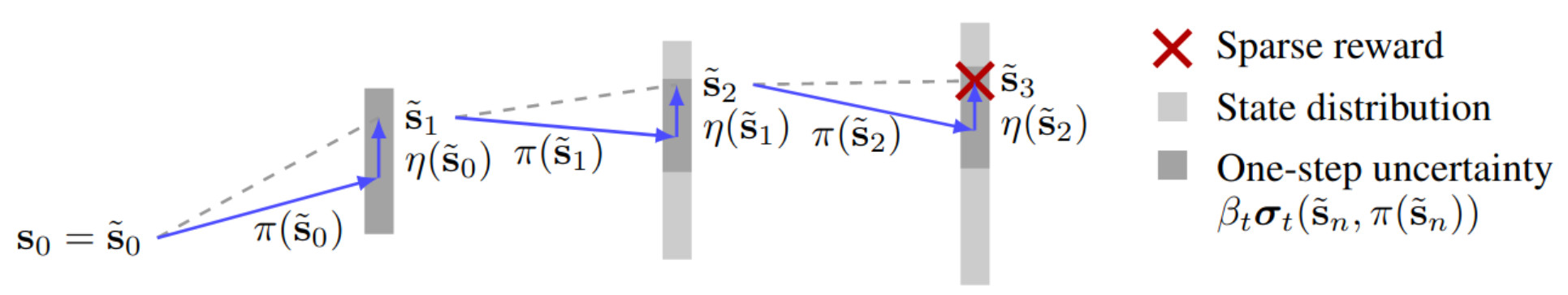

\[s_{t+1} = \mu_t(s_t, a_t) + \beta \, \sigma_t(s_t, a_t) \, \eta(s_t)\]We can visualize the difference between predictions according to samples from \(p(\tilde{f})\) and the optimistic dynamics under \(\eta\) below. For a given starting state \(s_0\), the distribution over possible transition dynamics induces a wide state distribution (light gray). In the case of sparse rewards (red cross), only very few of these transitions can obtain a positive reward. This causes greedy exploitation with \(\pi_t^\mathrm{greedy}\) to fail in the presence of action penalties. In contrast, H-UCRL can act optimistically within the one-step confidence intervals of our model (illustrated by vertical blue arrows within the dark gray area), so that the joint policies \((\pi, \eta)\) operate on a simpler, deterministic system that can be driven to the sparse reward exactly.

Intuitively, \((\pi, \eta)\) turn the stochastic distribution \(p(\tilde{f})\) into a simpler deterministic dynamic system that can be controlled easily (with large uncertainty \(\eta\) can influence the states directly). Thus, we optimize the two policies jointly,

\[\pi_t^{\mathrm{H-UCRL}} = \arg\max_\pi \max_\eta J(\tilde{f}, (\pi, \eta))\]under the extended dynamics

\[\tilde{f}(s, (\pi, \eta)) = \mu_t(s, \pi(s)) + \beta \sigma_t(s, \pi(s)) \eta(s) ,\]Note that while we optimize over \(\pi\) and \(\eta\) jointly, only \(\pi\) is applied when collecting data on the true environment \(f\). While the resulting \(\pi_t^{\mathrm{H-UCRL}}\) will not solve the task on the true system initially, it will collect informative data and converges to the optimal policy as the uncertainty \(\sigma(\cdot)\) in our model decreases (provably so in the case of Gaussian process models). At the same time, the optimistic formulation of H-UCRL fits into standard RL frameworks, where we just have a different dynamic system that includes an extended action space. This makes it easy to implement and code is available. Much more explanations and details can be found in the paper [1].

References

- Efficient Model-Based Reinforcement Learning through Optimistic Policy Search and PlanningSebastian Curi*, Felix Berkenkamp*, Andreas Krausein Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2020Spotlight talk

Model-based reinforcement learning algorithms with probabilistic dynamical models are amongst the most data-efficient learning methods. This is often attributed to their ability to distinguish between epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty. However, while most algorithms distinguish these two uncertainties for \em learning the model, they ignore it when \em optimizing the policy. In this paper, we show that ignoring the epistemic uncertainty leads to greedy algorithms that do not explore sufficiently. In turn, we propose a \em practical optimistic-exploration algorithm (\alg), which enlarges the input space with \em hallucinated inputs that can exert as much control as the \em epistemic uncertainty in the model affords. We analyze this setting and construct a general regret bound for well-calibrated models, which is provably sublinear in the case of Gaussian Process models. Based on this theoretical foundation, we show how optimistic exploration can be easily combined with state-of-the-art reinforcement learning algorithms and different probabilistic models. Our experiments demonstrate that optimistic exploration significantly speeds up learning when there are penalties on actions, a setting that is notoriously difficult for existing model-based reinforcement learning algorithms.

@inproceedings{Curi2020OptimisticModel, title = {Efficient Model-Based Reinforcement Learning through Optimistic Policy Search and Planning}, booktitle = {Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS)}, author = {Curi*, Sebastian and Berkenkamp*, Felix and Krause, Andreas}, year = {2020}, url = {https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.08684} } - Gaussian Processes for Data-Efficient Learning in Robotics and ControlMarc Deisenroth, Dieter Fox, Carl E RasmussenIEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 37, no. 2, 2015

Autonomous learning has been a promising direction in control and robotics for more than a decade since data-driven learning allows to reduce the amount of engineering knowledge, which is otherwise required. However, autonomous reinforcement learning (RL) approaches typically require many interactions with the system to learn controllers, which is a practical limitation in real systems, such as robots, where many interactions can be impractical and time consuming. To address this problem, current learning approaches typically require task-specific knowledge in form of expert demonstrations, realistic simulators, pre-shaped policies, or specific knowledge about the underlying dynamics. In this paper, we follow a different approach and speed up learning by extracting more information from data. In particular, we learn a probabilistic, non-parametric Gaussian process transition model of the system. By explicitly incorporating model uncertainty into long-term planning and controller learning our approach reduces the effects of model errors, a key problem in model-based learning. Compared to state-of-the art RL our model-based policy search method achieves an unprecedented speed of learning. We demonstrate its applicability to autonomous learning in real robot and control tasks.

@article{Deisenroth2015Pilco, journal = {IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence}, title = {Gaussian Processes for Data-Efficient Learning in Robotics and Control}, author = {Deisenroth, Marc and Fox, Dieter and Rasmussen, Carl E}, year = {2015}, volume = {37}, number = {2}, pages = {408-423}, doi = {10.1109/TPAMI.2013.218} } - Deep reinforcement learning in a handful of trials using probabilistic dynamics modelsKurtland Chua, Roberto Calandra, Rowan McAllister, Sergey Levinein Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2018

Model-based reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms can attain excellent sampleefficiency, but often lag behind the best model-free algorithms in terms of asymp-totic performance. This is especially true with high-capacity parametric functionapproximators, such as deep networks. In this paper, we study how to bridge thisgap, by employing uncertainty-aware dynamics models. We propose a new algo-rithm called probabilistic ensembles with trajectory sampling (PETS) that combinesuncertainty-aware deep network dynamics models with sampling-based uncertaintypropagation. Our comparison to state-of-the-art model-based and model-free deepRL algorithms shows that our approach matches the asymptotic performance ofmodel-free algorithms on several challenging benchmark tasks, while requiringsignificantly fewer samples (e.g., 8 and 125 times fewer samples than Soft ActorCritic and Proximal Policy Optimization respectively on the half-cheetah task)

@inproceedings{Chua2018HandfulTrials, title = {Deep reinforcement learning in a handful of trials using probabilistic dynamics models}, author = {Chua, Kurtland and Calandra, Roberto and McAllister, Rowan and Levine, Sergey}, booktitle = {Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS)}, pages = {4754--4765}, year = {2018} } - Certainty equivalence is efficient for linear quadratic controlHoria Mania, Stephen Tu, Benjamin Rechtin Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019

We study the performance of thecertainty equivalent controlleron Linear Quadratic(LQ) control problems with unknown transition dynamics. We show that for boththe fully and partially observed settings, the sub-optimality gap between the costincurred by playing the certainty equivalent controller on the true system and thecost incurred by using the optimal LQ controller enjoys a fast statistical rate, scalingas thesquareof the parameter error. To the best of our knowledge, our result is thefirst sub-optimality guarantee in the partially observed Linear Quadratic Gaussian(LQG) setting. Furthermore, in the fully observed Linear Quadratic Regulator(LQR), our result improves upon recent work by Dean et al.[11], who present analgorithm achieving a sub-optimality gap linear in the parameter error. A key partof our analysis relies on perturbation bounds for discrete Riccati equations. Weprovide two new perturbation bounds, one that expands on an existing result fromKonstantinov et al. [25], and another based on a new elementary proof strategy.

@inproceedings{Mania2019Certainty, title = {Certainty equivalence is efficient for linear quadratic control}, author = {Mania, Horia and Tu, Stephen and Recht, Benjamin}, booktitle = {Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems}, pages = {10154--10164}, year = {2019} }